IPFS

Menckens Ghost

More About: Economy - Economics USAA Livable Wage Then and Now

In 1907, in Pittsburgh, in the heart of the American Industrial Revolution, furnace keepers in steel mills worked 84 hours a week, for an hourly wage of 23 cents, or in today's inflated dollars, $5.92 per hour.

In 1926, the same furnace keepers worked 55.5 hours per week, for an hourly wage of 63 cents per hour, or in today's inflated dollars, $8.53 per hour.

The increase in pay over those nine years was due to productivity increases; specifically, more steel was produced with fewer workers, due to mechanical advancements, such as motorized conveyer belts that fed ore and coke to furnaces, which eliminated the jobs of wheelbarrow pushers. (Today, productivity is basically flat-lined, which in turn results in flat-lined pay.)

It also helped that Europe was still recovering from the carnage and economic costs of the First World War, and China and other future competitors were still largely unindustrialized.

Some say that $8.53 is not a livable wage today. Yet in 1926, not only did urban workers raise large families on such a wage, but they did so before the advent of the welfare state and the two-income family.

This was possible in large part because taxes were not at confiscatory levels in 1926. Back then, government at all levels (city, school district, state, federal) took about 12% of national income. Today, they take nearly 50%, not counting the tremendous but unseen cost of complying with ever-growing regulations.

Granted, workers in 1926 didn't have cellphones, big-screen TVs, air-conditioning, Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, penicillin, polio vaccine, ultra-sounds and MRIs, open-heart surgery, cars with automatic transmissions and power windows, large apartments and houses, frost-free refrigerators, cross-country travel by jet, supermarkets with year-round fresh fruit and vegetables from around the world, fast-food restaurants of every description, domed stadiums, Disney World, or four-dollar lattes at Starbucks.

In today's service economy, on the other hand, low-wage service workers have all these things, in spite of the conventional wisdom that globalism, immigration, and the offshoring of manufacturing jobs have left working-class Americans in dire economic straits and with a declining standard of living.

So what's the truth about today's economy? Is it good or bad, on the downswing or upswing, stacked against the working class or stacked in favor of the capital class? Is our standard of living improving or deteriorating? Is the America dream over, or are we on the verge of technological advances that will bring untold improvements in the quality of life?

For a politician or for a pundit or talk-radio host playing to his audience, the truth doesn't matter. All that matters is the perceptions of voters. And for a large segment of voters, the perception is that the nation is in the toilet.

Putting that perception aside, what is the truth about the economy?

To answer that question in sufficient detail would require more depth and more time than an episode of TMZ or a YouTube video, which are the cognitive limits of most Americans nowadays. Not only that, but the answer depends on what variables are being considered, what time frames, and the definitions of such seemingly simple words as "income."

On the last point, for example, when comparing income from one period to the next, here are the questions that should be asked and answered to get a fair, non-ideological comparison:

Is income pre- or post-tax?

Is it real income (inflation-adjusted) or nominal income (not inflation-adjusted)?

Is it per-capita income or household income (which has declined significantly due to the rise of single-parent, single-earner households)?

What is counted as income? Pay? Investment income? Transfer payments (welfare, entitlements, unemployment compensation, disability payments)?

Does income include estimates of unreported income and illicit income?

What are the features and quality of goods and services that a dollar buys today versus what a dollar bought in the past?

If a Salvadoran immigrant crosses the U.S.-Mexico border illegally, and by doing so increases his daily income 500% but earns eight dollars an hour in the States, is he now wealthy or poor?

Well, I've lost the TMZ crowd with those questions.

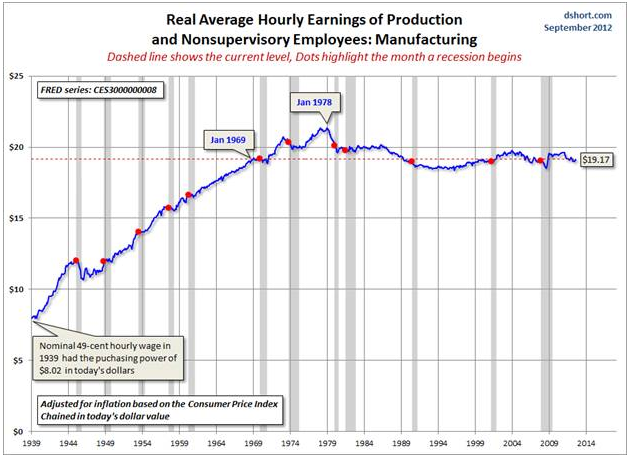

The conventional wisdom is that income has declined over the last decade for unskilled Americans who do not work in high-wage manufacturing and do not have a college education. After considering the variables listed above, there is considerable evidence that incomes for this segment of the labor market have flat-lined and even declined. But few babble heads mention this: Inflation-adjusted earnings (pay) of manufacturing workers have been flat for the last 38 years, as shown in the chart below.

The chart shows that until 1978, earnings rose steadily, except during recessions.

What accounted for the rise for all those decades? The answer is a confluence of favorable factors unlikely to be repeated again.

First, in the early 20th century, there was massive immigration of cheap labor to American cities from Europe, from American farms and from American blacks moving from the South to the industrialized North. This cheap labor, combined with cheap energy, other abundant natural resources, technological advancements, low taxes, and relatively free markets, resulted in huge productivity gains, which in turn resulted in higher wages.

Second, as mentioned earlier, Europe was still recovering from the cost and carnage of the First World War, and China and other future competitors were largely unindustrialized. Also, Europe was beset by political unrest and Communist-dominated labor unions. Then, after the Second World War, most of the world was devastated, with the notable exception of the U.S.

So why did the rise slow down and stop in the 1970s?

One reason is that the favorable factors had run their course. Most notably, Europe and Japan had risen from the ashes, third-world countries were beginning to industrialize, and the U.S. was no longer the leading oil-producing country in the world.

Other possible causes are mostly conjecture and impossible to isolate and prove.

One possibility is the deficit spending that resulted from the cost of the Vietnam War and from Nixon closing the gold window and removing the last obstacles to the printing of fiat money.

Another possibility is the cultural upheavals of the Sixties and the advent of the welfare state and regulatory state.

Still another is married women entering the workforce, which was a double-edged sword, with both benefits and drawbacks for the economy and society. For lower socioeconomic classes, it resulted in a rise in out-of-wedlock births and single-mother families. For higher socioeconomic classes, it resulted in marriages between high-income, college-educated professionals, which in turn resulted in their household income skyrocketing.

At the same time, the tradition of noblesse oblige had waned. Due to the burgeoning welfare state, the wealthy no longer felt obligated to be benevolent and paternalistic to the less fortunate, to socialize with people outside of their social class, or to enter government service at the relatively low pay, benefits and perquisites that existed in the past but no longer today.

Meanwhile, the rise of illicit drug use and the War on Drugs increased the rates of crime and incarceration, leaving millions of Americans unemployable or employable only at the margins of the job market.

The advent of the credit card didn't help matters. Savings fell and indebtedness rose. Consumer spending became a patriotic duty, and a consumption economy replaced a production economy.

All the while, government bureaucracies did what government bureaucracies do: They multiplied like fruit flies, resulting in the growth in government employment far exceeding the growth in the population at large. For example, if the growth of government jobs (including teachers) had kept pace with the growth of the general population instead of exceeding it, there would be about 12 million fewer government workers today. Assuming a totally-loaded cost (pay, benefits, overhead) of $120,000 per worker, that comes to $1.4 trillion in taxes taken from private-sector workers to support the extra government workers.

So how do we make America great again? Well, a prerequisite is to be honest about the facts, because sound solutions require sound analysis.

Good luck with that in today's ideological divide and TMZ attention span.

For sure, we know what will not make America great again: the erection of border walls and tariff walls. These will only exacerbate the nation's economic and class problems. Unfortunately, to explain this would require as much time as three episodes of TMZ combined. And to comprehend the explanation would require five times the intelligence it takes to watch a presidential debate and ten times the intelligence it takes to listen to Donald Trump.